From Streams to Drains

“Where does this water come from?” a young girl asks, eyes widening with curiosity as she peers down at the water flowing from an underground pipe into the lake. Answers as simple as “the clouds” or “the sky” fail to explain that it is all connected in a cycle that makes a cloud, the sea, and everything in between home, at least for a little while.

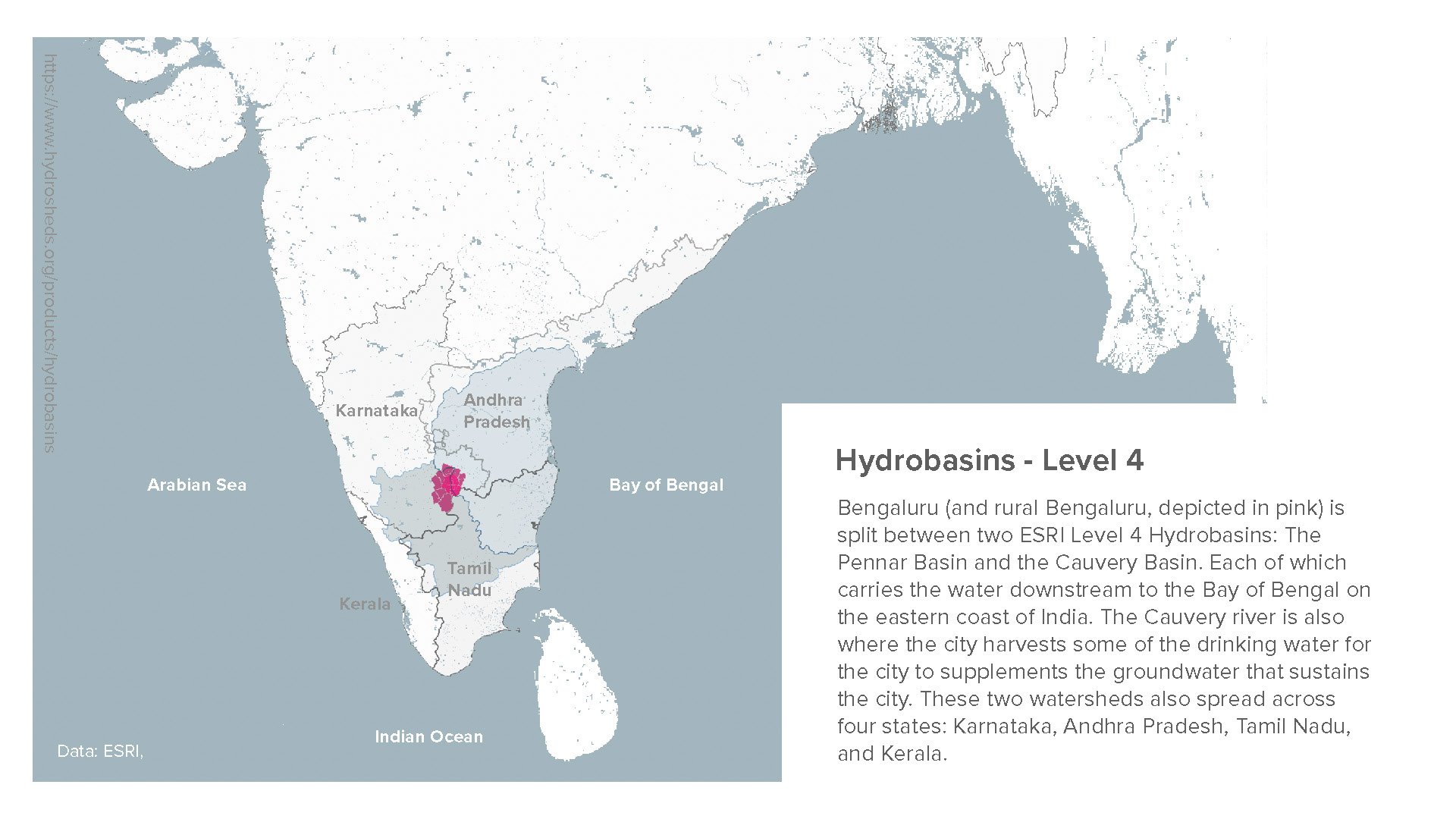

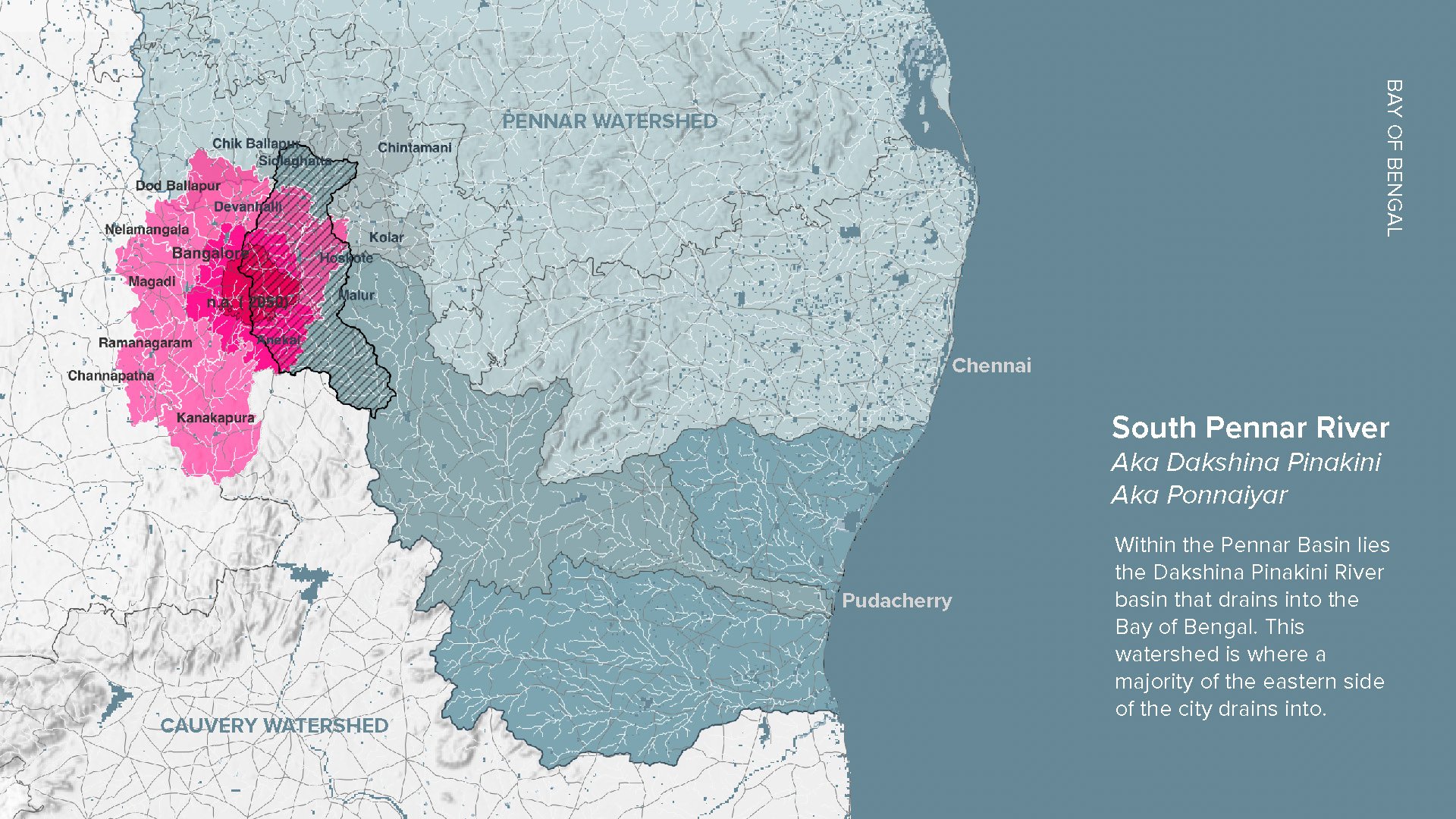

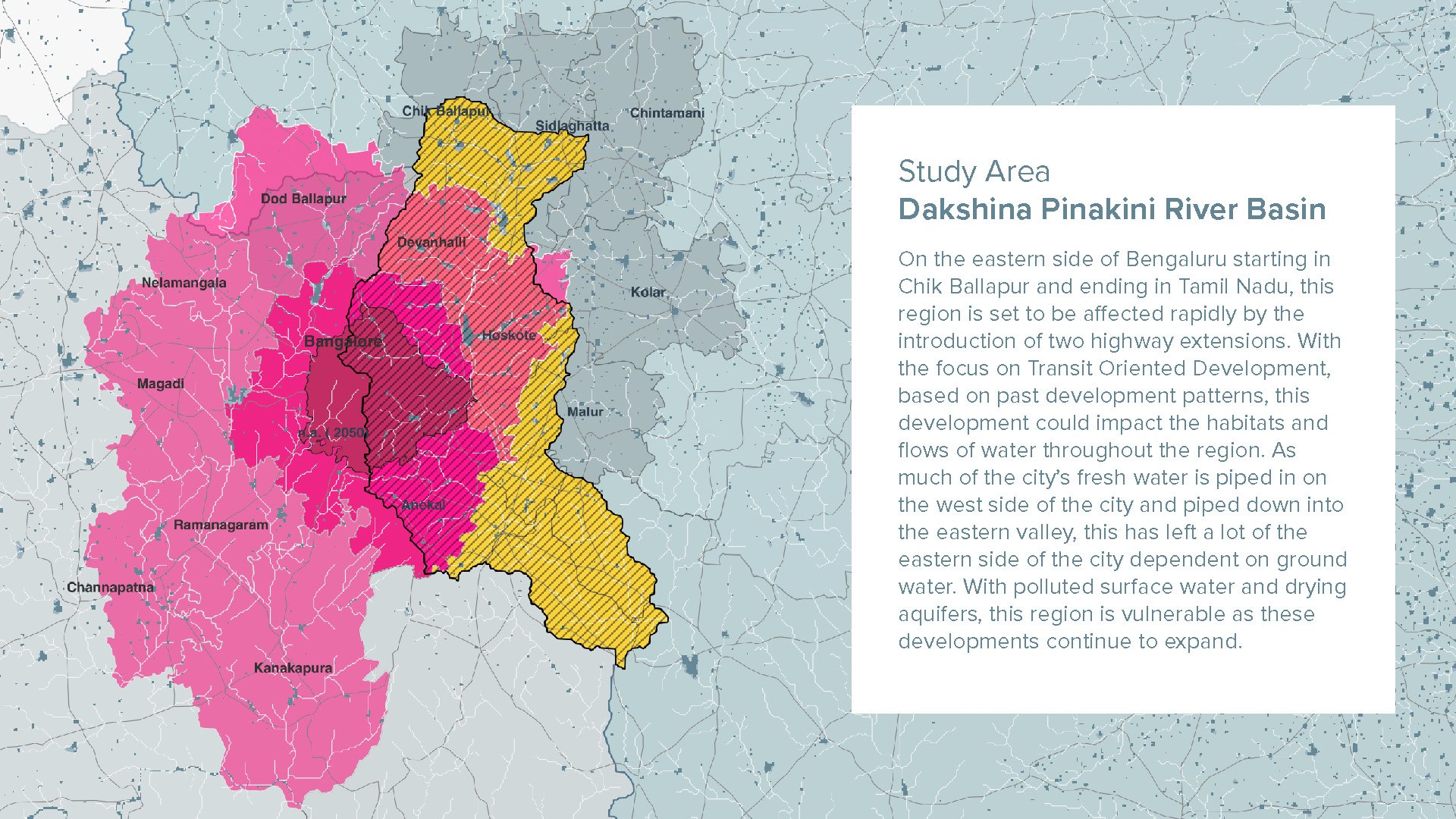

Over the last month, I’ve been exploring the water systems of Bengaluru. I’ve been questioning: What does water resilience look like for a rapidly growing city not near to a large freshwater source like a river? Where does our drinking water come from? Where does it go? How does the city manage it from sky to sea?

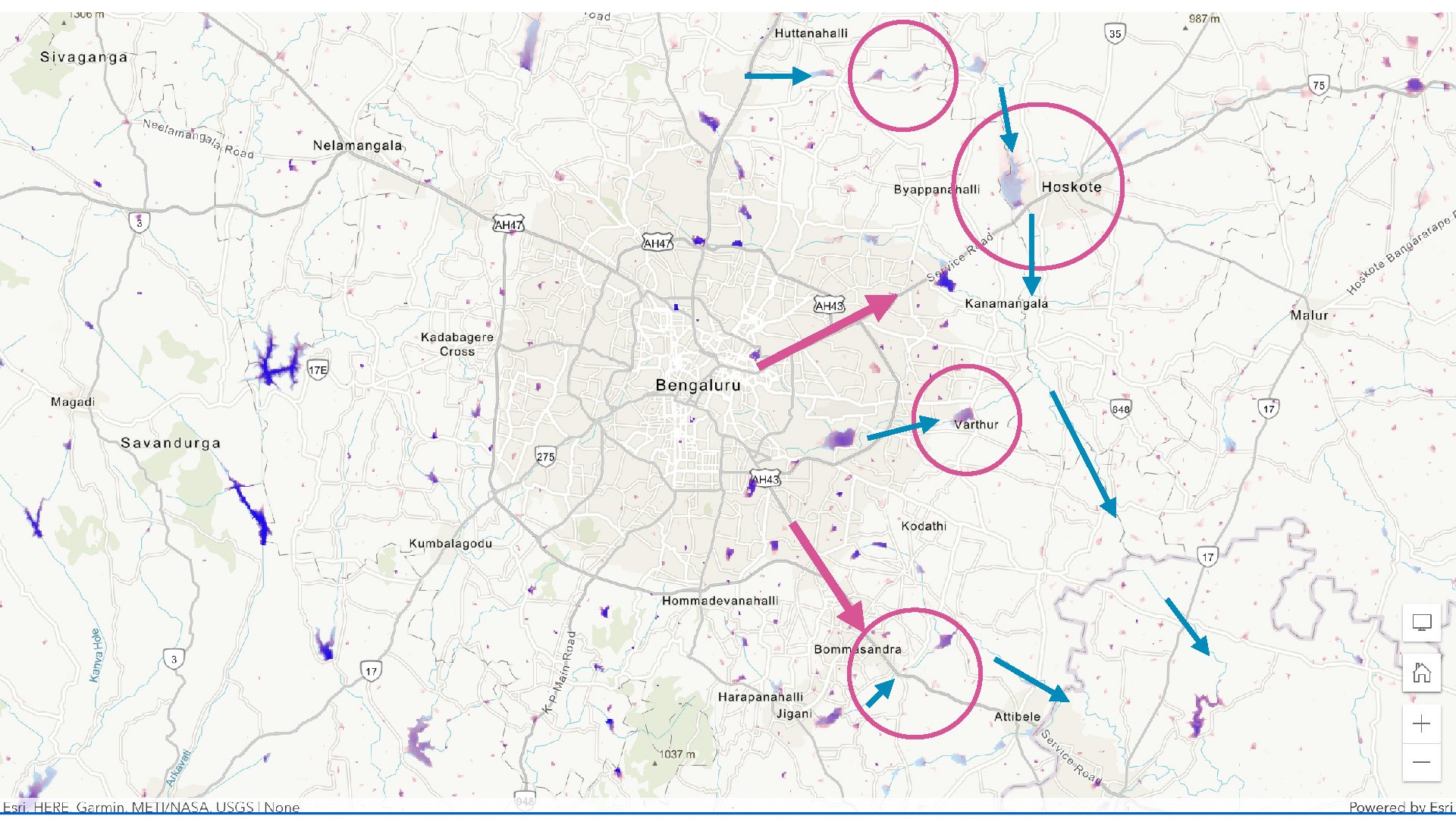

This curiosity has led me (digitally) to trace the landscape from the peaks in the Western Ghats all the way down to the mouth of the rivers into the Bay of Bengal and (physically) to muddy edges of “stormwater” drains that snake through the city to water-holding tanks (fondly called “lakes”) wrapped in parkland and threaded walking paths, to conversations with local water activists on the resilience of the water system. My questions remain: will Bengaluru “run out of water” as predicted? What are the factors involved in making this system (or systems, rather) more resilient? What latent potential lies within the investments set to be made in the coming years for the city’s infrastructure?

This work started over a decade ago as I questioned the potential synergies between human development and the natural environment. When I first learned about the “Anthropocene”—the current geological epoch describing the imbalance of impact from human to non-human systems—I became interested in the role of design in resetting this imbalance. Over the last century, throughout our global landscape, we have altered landscapes through dams, levees, deforestation, water diversion, mining, and so much more. We have drastically changed the way global ecosystems function with the “advancement” of our societies. These changes large and small have a ripple effect on the livelihoods of people and every other living being on our planet. We have enlisted the environment as our employee and our payment has often been devastation. Somehow I remain hopeful that we can do something about it. If we can use the brilliant technology being created for good, can we save our dying planet? I wonder.

When I first arrived in Bengaluru, one of the many things that astounded me was the life that lined the streets. Vendors serving tender green coconut, children playing, elders taking a rest on the doorsteps, and people enjoying a conversation under the massive trees. I became fascinated by the “storefront” that was alive and active in a way you just don’t see in the US. One Saturday morning when I was walking to the grocery store, I saw a sidewalk being constructed, everything is under construction these days. As I looked down, I saw a small stream of water. Curious, I started following it to a large concrete drain at the edge of my street. When I got to its edge, I looked upon the water, the grasses, and the waste that had been washed from these bustling streets down into the drain. This happens all over the world. Underground systems of “stormwater management” hide it from plain sight in most cities. Here, it is open. It is visible. And yet, people seem to ignore it. It has become a smelly backdrop that is just part of the urban landscape. I remember taking a photo while on a walk with a friend and he questioned… why are you taking a picture of the drain. I said, “research.” But in my heart, I knew it was more than that. I saw an opportunity to talk about this connectivity of water in a new way. I saw the hope of turning this space into something that could do more for the city, more for the natural environment than just carry stormwater elsewhere.

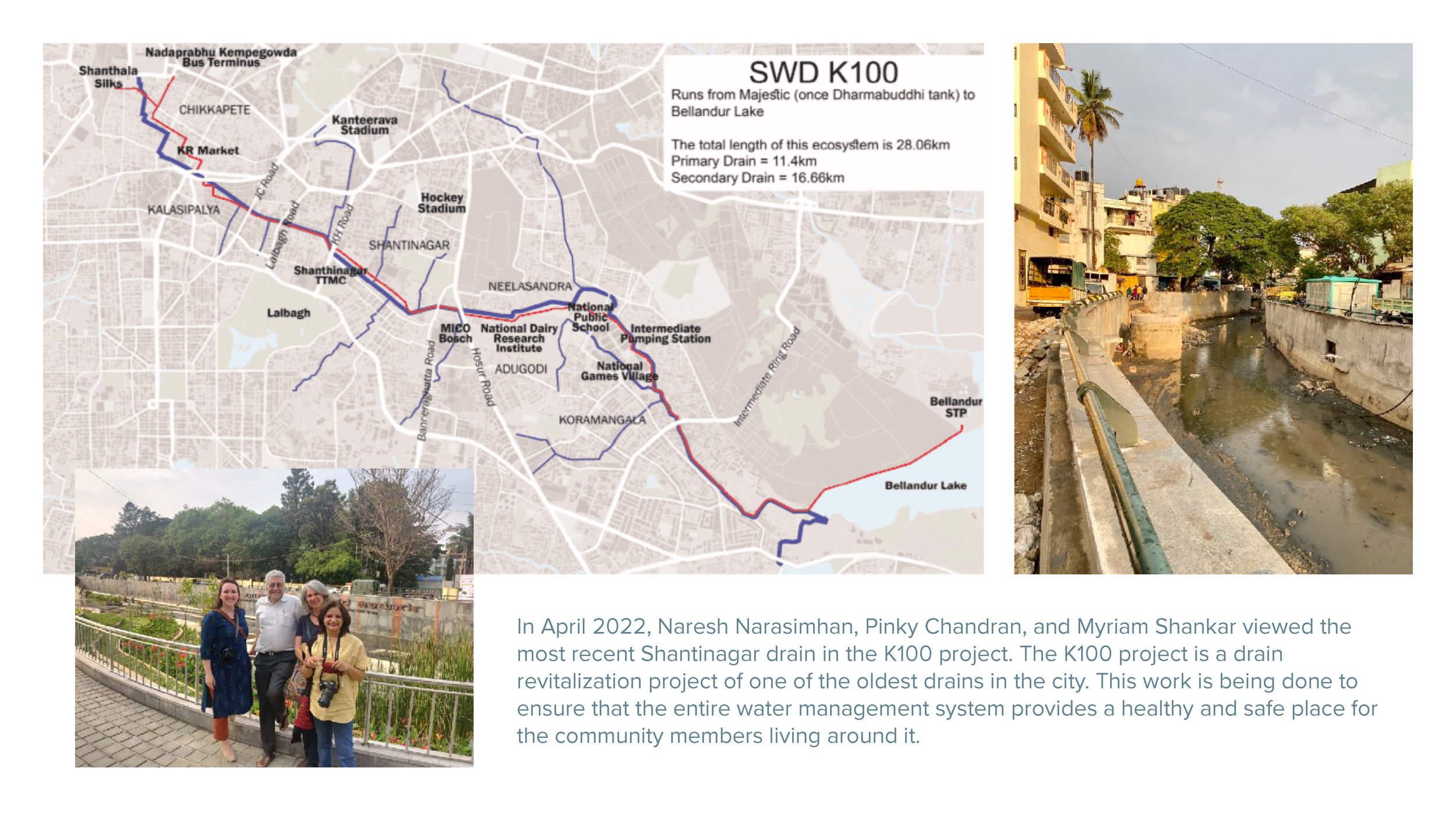

After doing some digging on water infrastructure projects and exploring a lot of lake restoration movements, I came across the K100 Project (aka the Citizens’ Water Way project) which was set to “rejuvenate a 12-km-long network of stormwater drains that links Majestic, in the heart of Bengaluru, to Bellandur Lake” (well-known for its polluted state). It was exciting to see a comprehensive look at lake health because ultimately any catchment system, whether it is a pond, lake or otherwise, cannot be truly “clean” unless the entire basin is also clean. And for growing cities like Bengaluru, that can be a challenge. The K100 project has been met with a lot of challenges. For one, the stormwater drains have been carrying much more than stormwater so cleaning them up has required interventions on sewage management within this 12km corridor and throughout the entire watershed. There were hundreds of pipes releasing human waste and chemical waste directly into these drains. The second issue was dry waste management, ie loads of plastic bottles, wrappers, food containers, and more that lined the surface of the water and clogged the drains as it collected in the more narrow spots.

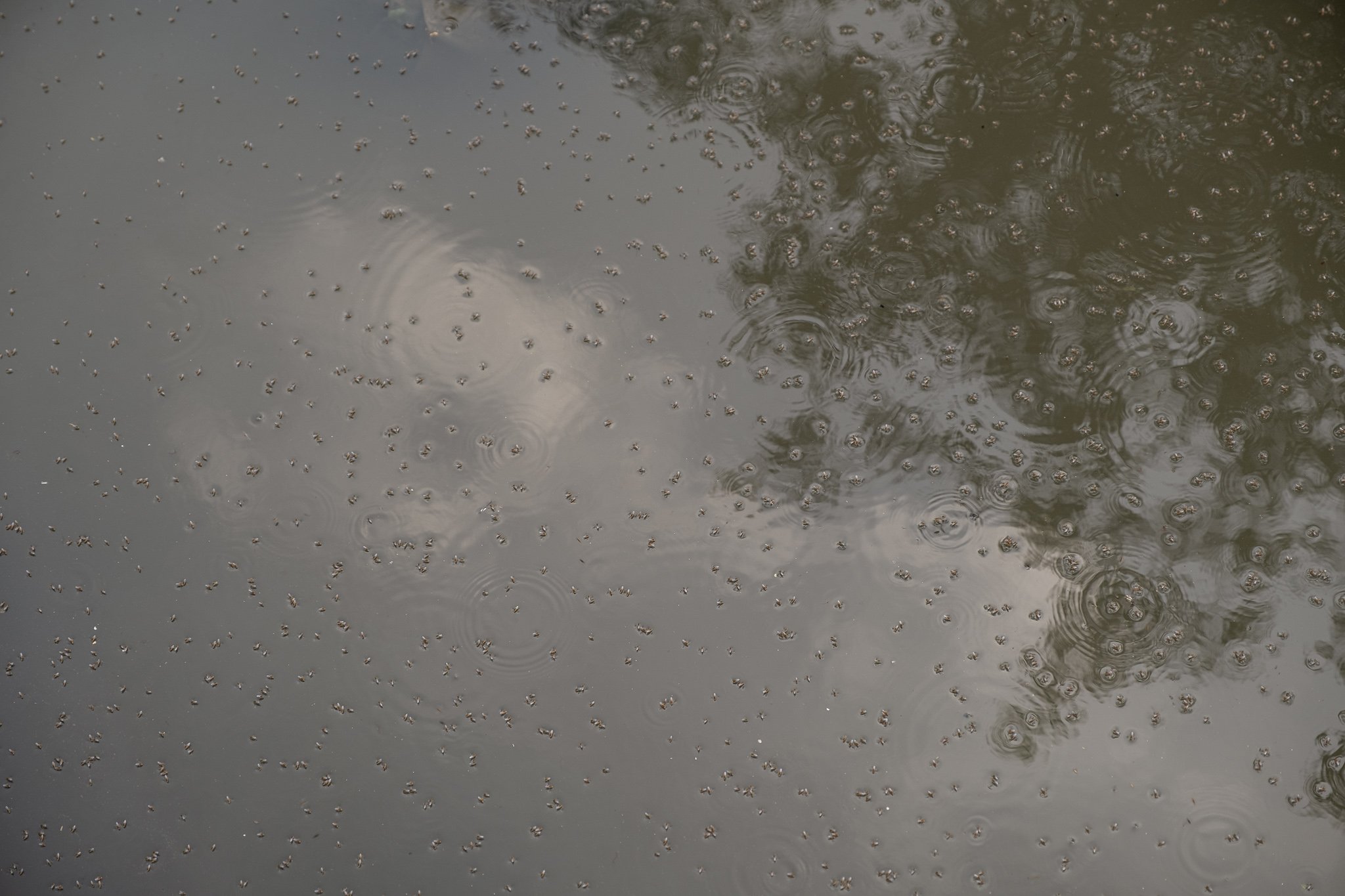

I met with the primary architect, Naresh Narasimhan, who took the three of us: Pinky, Myriam, and me on a tour of the most recently completed segment in Shanthinagar near KH Road. Descending the ramp lined by large lush plants into a terraced landscape of concrete and flowers, we found the drain once again but definitely with a facelift. I mean, you could access it for one without having to scale the wall. That was a start. We could see some of the issues they were facing with the redevelopment in glistening golden light. Silt and trash had collected on the stairs and paths from the previous night’s storm. The rain fell hard and raced through the streets, washing everything in its path to these drains, sometimes far from its original location. At the edge of the drain’s edge, we discussed that the entire catchment must be clean to ensure our drains, lakes, and rivers are clean and unpolluted. But how? How do we tackle the massive issues of waste management in a growing city like Bengaluru? And there, the next challenge remains: waste.

Moments later, as if she had heard us call her name, our discussion was punctuated as the day’s heat burst into raindrops, reminding us that if we don’t keep it clean, she will, but she won’t be discrete about it. It all goes.

Bringing it full circle, I am so excited to announced that I’ll be helping to develop the Rivers of Life exhibition for Azim Premji’s Centre for Climate Change and Sustainability which will open in August - September 2022. Special shoutout to amazing co-pilot in that Kunal. Thanks for being your fullest whacky creative lover of trees self.

If you know of someone who is working on a photojournalism or documentation of the Indian river ecosystems, livelihoods supported by rivers, threats, or organizations making an effort to protect them, let me know.