Designing for Dynamism

As the name implies, “fluxscapes” are described as landscapes in fluctuation: shaped by water, climate, migration, politics, and other dynamic factors. Urban landscapes as they are designed today, often cannot respond to such rapidly changing systems. With innovations in technology, we can now build more resilient cities for the generations to come by integrating sensing mechanisms, crowd-sourced data, and machine learning techniques to anticipate and design for these ever-changing systems.

RESEARCH

FLUX: Strategies for resilient Peri-Urban development

Ridge + Valleys of Bengaluru — Data: KGIS, HydroSheds, SRTM DEM from Google Earth Engine, Lakes from OpenCityData + adjusted by author.

Flowing east from the growing city of Bengaluru, the Dakshina Pinakini River Basin conveys water into the Ponnaiyar River then through Tamil Nadu, and into the Bay of Bengal. This landscape is home to many farms and lakes holding water and recharging the aquifers for the communities within its catchment. Originating in Nandi Hills, the river weaves through the valleys and is fed by a series of cascading lakes from the east and west. For centuries Bengaluru has depended on the cascading lake system for water holding either for agricultural irrigation, drinking water, or other socio-ecological functions. This cascading lake system has become disconnected in parts and polluted heavily by the city’s waste and wastewater.

In this study, FLUX examines the land use change, and projected land use change as proposed by the most recent Masterplan (subject to change in its second revision) and assesses the potential for integrating multi-functional infrastructures that can serve ecological functions as well as increase water and food resilience for the coming years.

Much of the water for Bengaluru’s growing population is supplied via a 1000km long and 100m high pipeline from a series of dams along the Cauvery/Kaveri River. This steep climb requires a lot of power for the pumping station and does not fully meet the needs of the citizens within the BBMP boundary much less the Regional area of planning. Borewells and other groundwater extraction mechanisms are used throughout the peri-urban to supply water to citizens. Some homes even have piped water in addition to borewell water. On April 21, 2017, the Bangalore Water and Sewerage Supply Board (BWSSB) made it mandatory that large apartment buildings and IT parks have their own Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) and issued a “zero discharge” requirement for treated wastewater. As these complexes multiplied throughout the city, an excess of wastewater also grew exponentially, sparking an entrepreneurial spirit in the wastewater sector.

In the area of study along the three eastern valleys that flow into the Dakshina Pinakini, the city is projected to grow in this region which has already had issues with contaminated groundwater and depleting groundwater supply. With the addition of nearly 6 million new inhabitants to the city, the pressure on the groundwater of this region will increase, deeply impacting the communities that depend on it for agriculture and drinking water.

FLUX explores transitional planning strategies for building water resilience in this region. The peri-urban serves as a great testing ground for such explorations as it does not have the constraints of dense existing infrastructure. The goal of this project is to examine the role of landscapes of recharge as a mechanism for building water resiliency which in turn will impact the food security of this region.

Contact for Download Link

TESTING GROUNDS

001 — Re-streaming the Rajakaluves in the Yele Mallappa Shetty + Hoskote Lake Catchment

Hebbal Valley

Located in Northeast Bengaluru, near Whitefield, the Yele Mallappa Shetty Lake dates back to the early 1900s and spans nearly 500 acres. It is part of a series of constructed tanks that flow into the Dakshina Pinakini (Ponnaiyar) River that empties into the Bay of Bengal in Tamil Nadu.

Hoskote Lake, which is northeast of Yele Mallappa Shetty Lake on NH75 toward Chennai and is part of the natural flow of the Dakshina Pinakini River. Each lake system is connected by a series of feeder channels called kaluves or rajakaluves. In the literature, it was clear that the tanks were built to support the growing population but now are suffering due to the influx of effluent and waste pollution being dumped into their wetlands.

Research Question: How had development impacted lakes? How could design be utilized to support the ecology of the lakes and create water-sensitive urban solutions as the city expands?

Yele Mallappa Shetty lake — 2004 to 2022, source: Google Earth Pro

Hoskote Lake — 2007 to 2022, source: Google Earth Pro

002 — Filter · Flood · Flow · Food Landscape In the KC Valley

Koramangala-Challaghatta Valley

One main concern in building a “water resilient city” is the introduction of pollution to the water system, especially a city that is highly dependent on groundwater. Bengaluru pipes a majority of its water supply from the Cauvery, nearly 500m uphill then dispurses it through a series of pipes to the perimeter of the city. It is estimated that 40% of the water is lost to leakage. Additionally, the water once it is utilized is sent to treatment plants that process and disperse the treated water once more to fill lakes within the peri-urban regions of Anekal, Chikballapura, and Kolar.

One concern found during fieldwork was the impact that the pollution has on the agricultural sector and the additional pollution caused by the sector itself with the use of chemical fertilizers. In this section of the project, I examine the role of biofiltration systems through plants and landforms to filter the water before it gets to the streams. This will hopefully impact the ecological landscape and the crops being grown to produce a healthier, more resilient region.

Research Question: What is the role of landscape architecture to filter pollution, manage floods, and allow for the slow flowing of water into the valley for recharge?

003 — Ground/Water Park in Anekal

Chinnar Valley

As the city has grown from 6 million in 2002 to 16 million in 2022, the development has spread throughout the landscape. One area, in particular, became a hot spot for growth due to the influx of IT companies setting up offices in Bengaluru in the 2000s. “Electronic City” as it is now known was predominately agriculture near the turn of the century. Now home to an ever-expanding population, the urban zone is set to expand even further along NH44 toward Hosur. The most recent master plan proposes a strategy called “clustering” where peri-urban cities like Hoskote and Hosur become “hubs” for transportation and commerce.

The proposed “ground/water” park would consist of a community commons + centre that could house citizen action activities around the lakes, groundwater, farming, and other ecologically sensitive discussion topics. Citizens could come and learn from one another on best practices for watering crops, managing their personal gardens, and discuss groundwater protection strategies when recharging.

Research Question: With peri-urban communities so dependent on groundwater and Bengaluru struggling to provide piped water to the eastern part of the city, how can we design systems of groundwater management into the architecture and landscape architecture of the region?

Deep Surface: Engaging the Terra Viscus

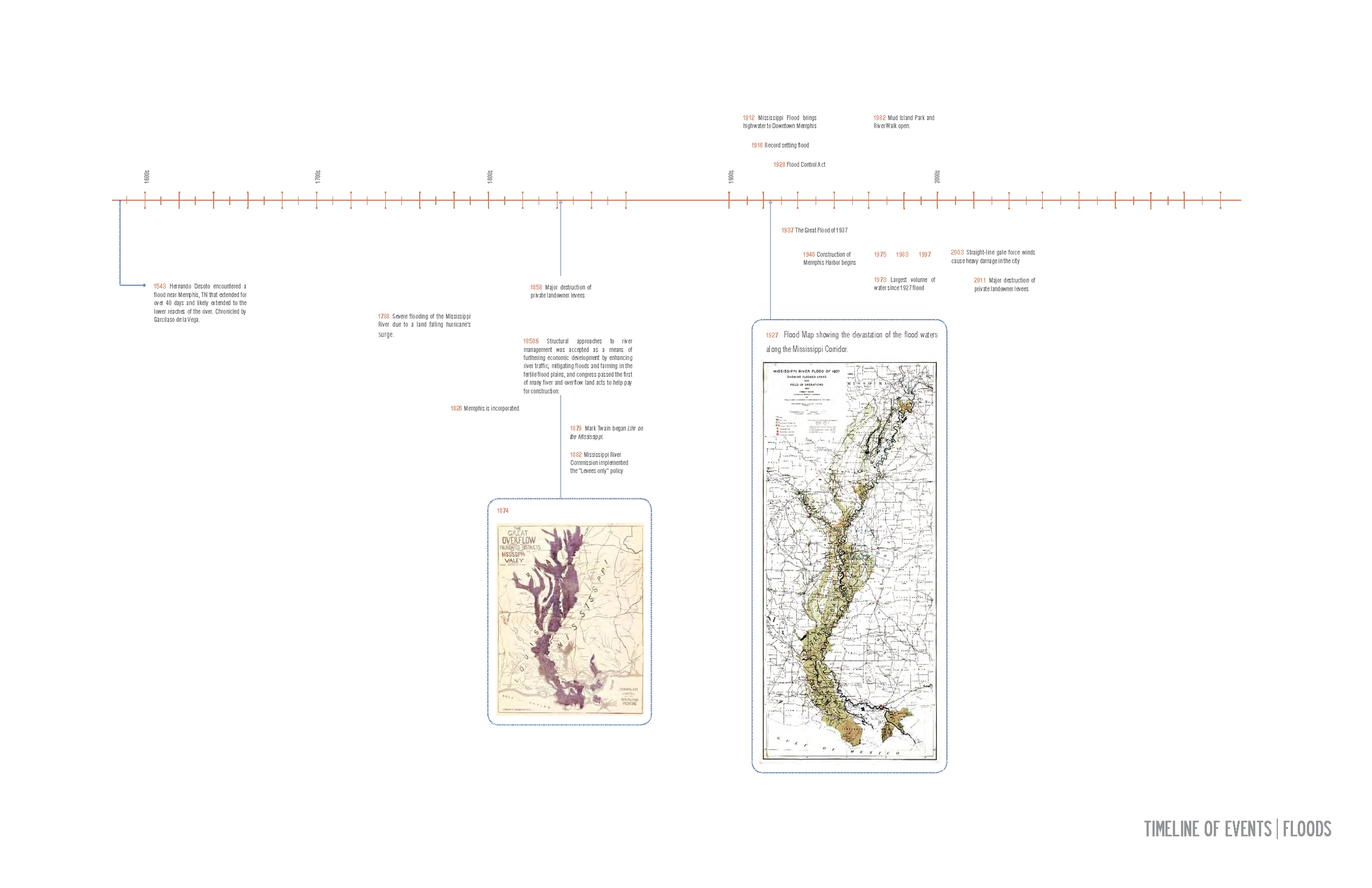

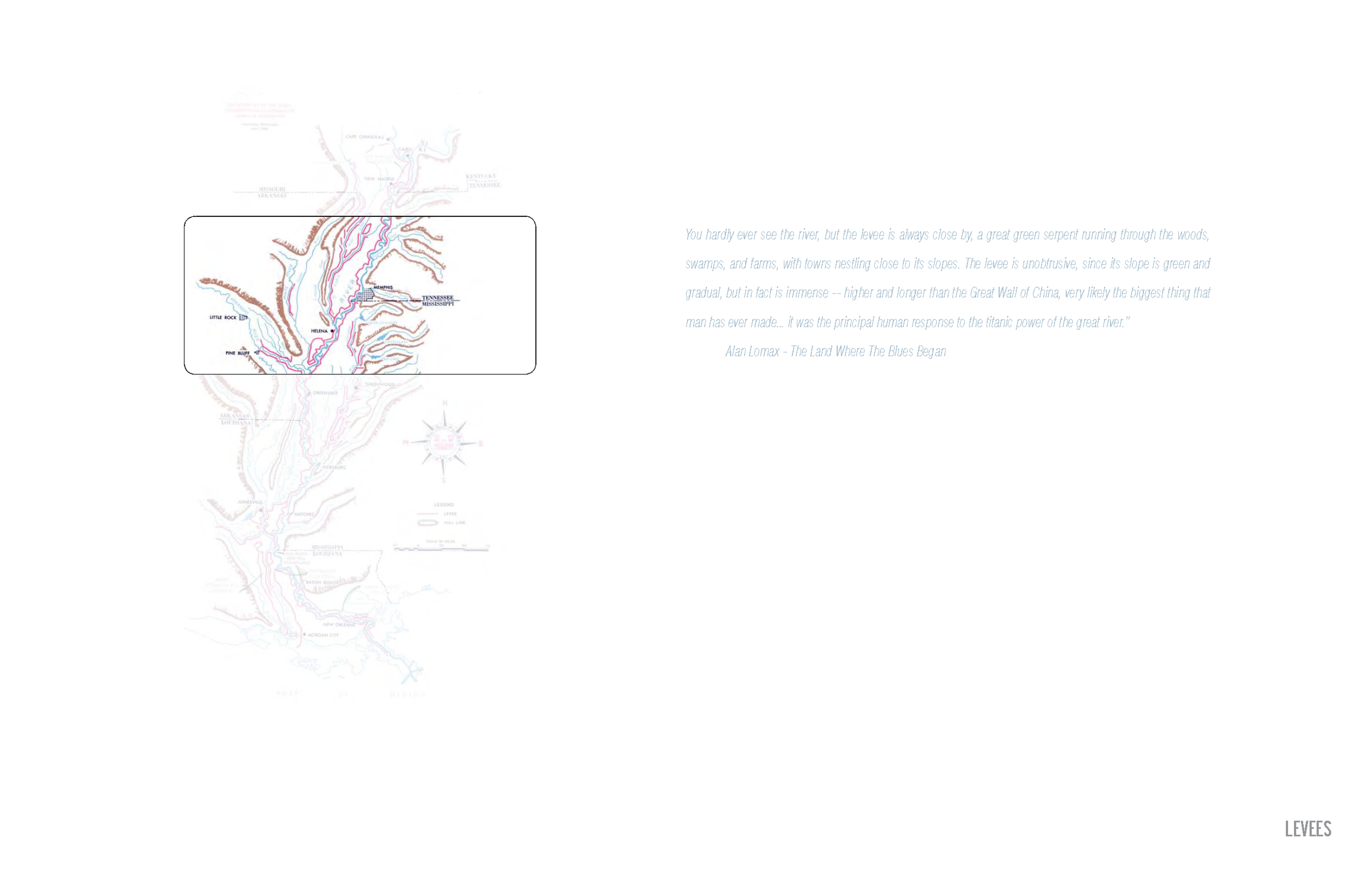

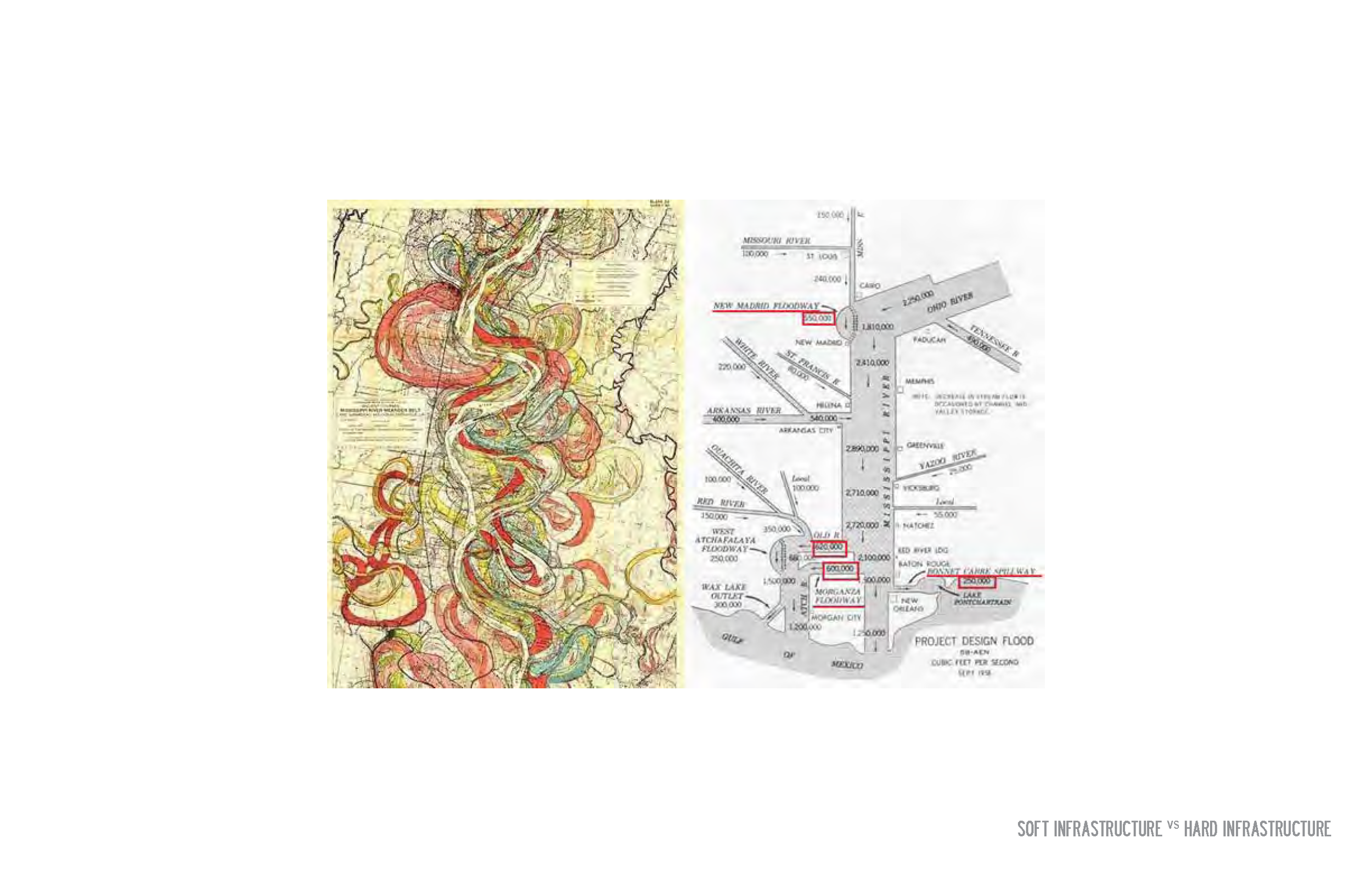

Graduate Thesis Project - Masterplan for Memphis, TN

Graduate thesis project

May 2014 - Master of Science in architecture / Sustainable Landscape Urbanism

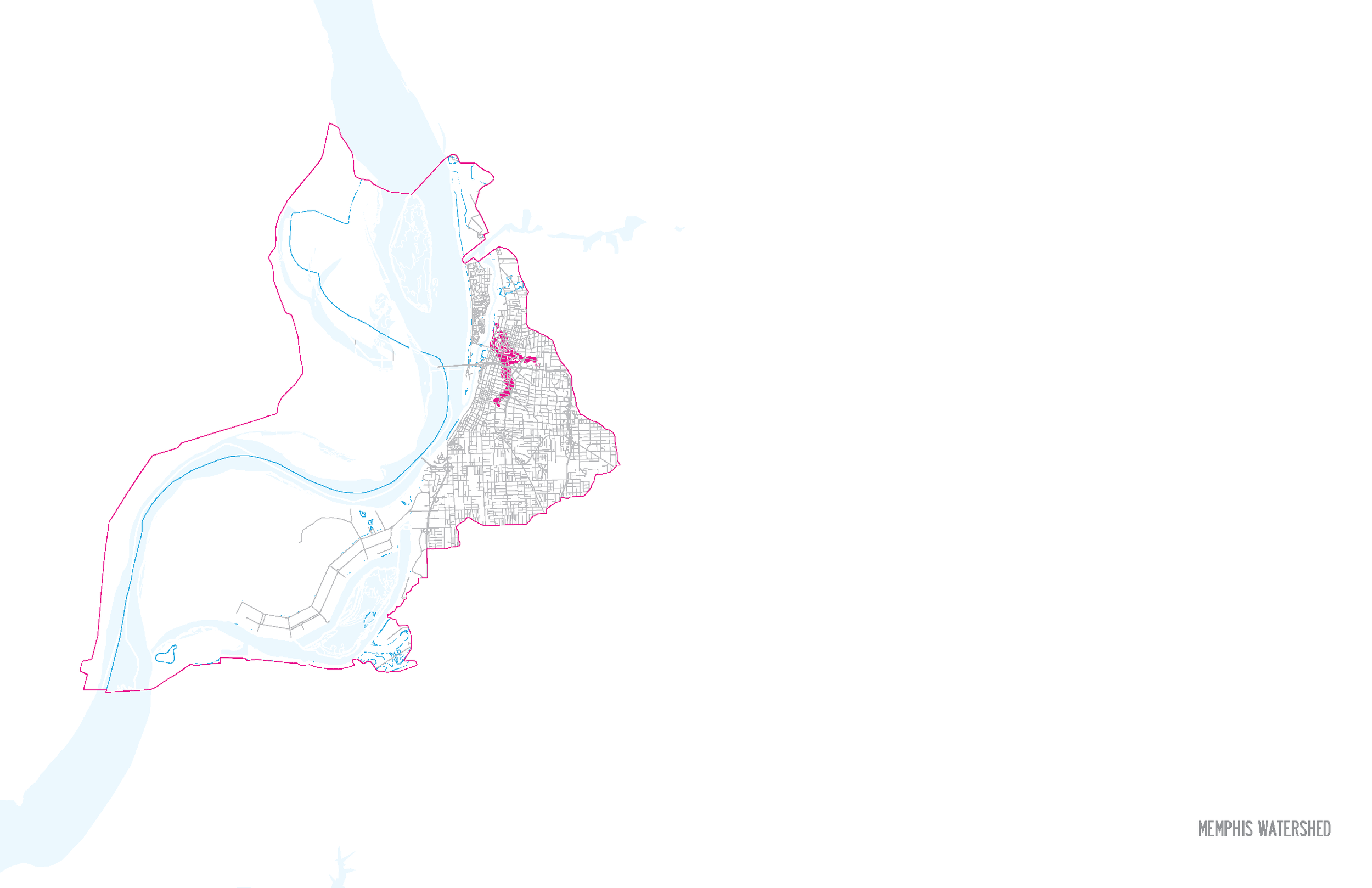

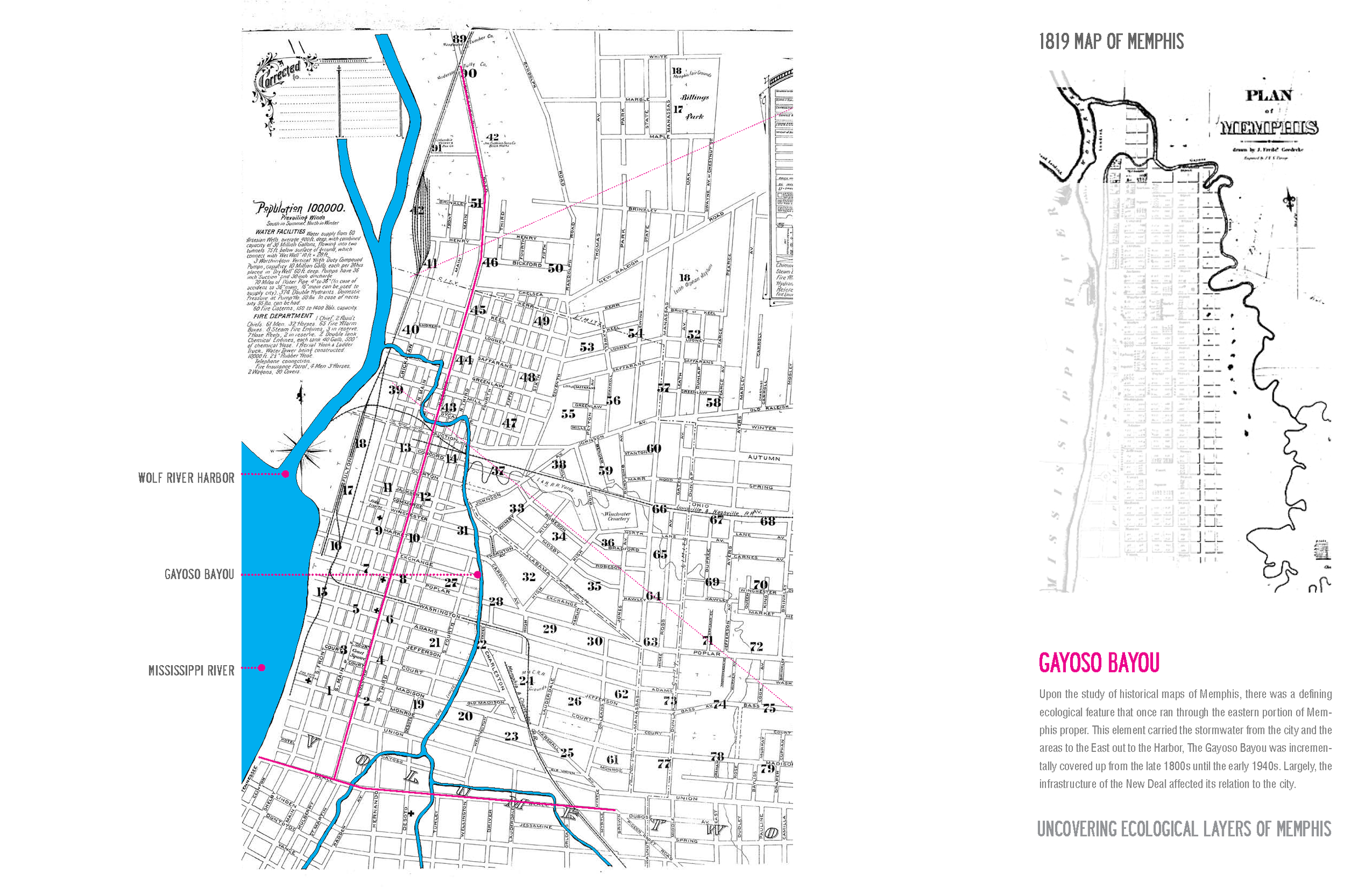

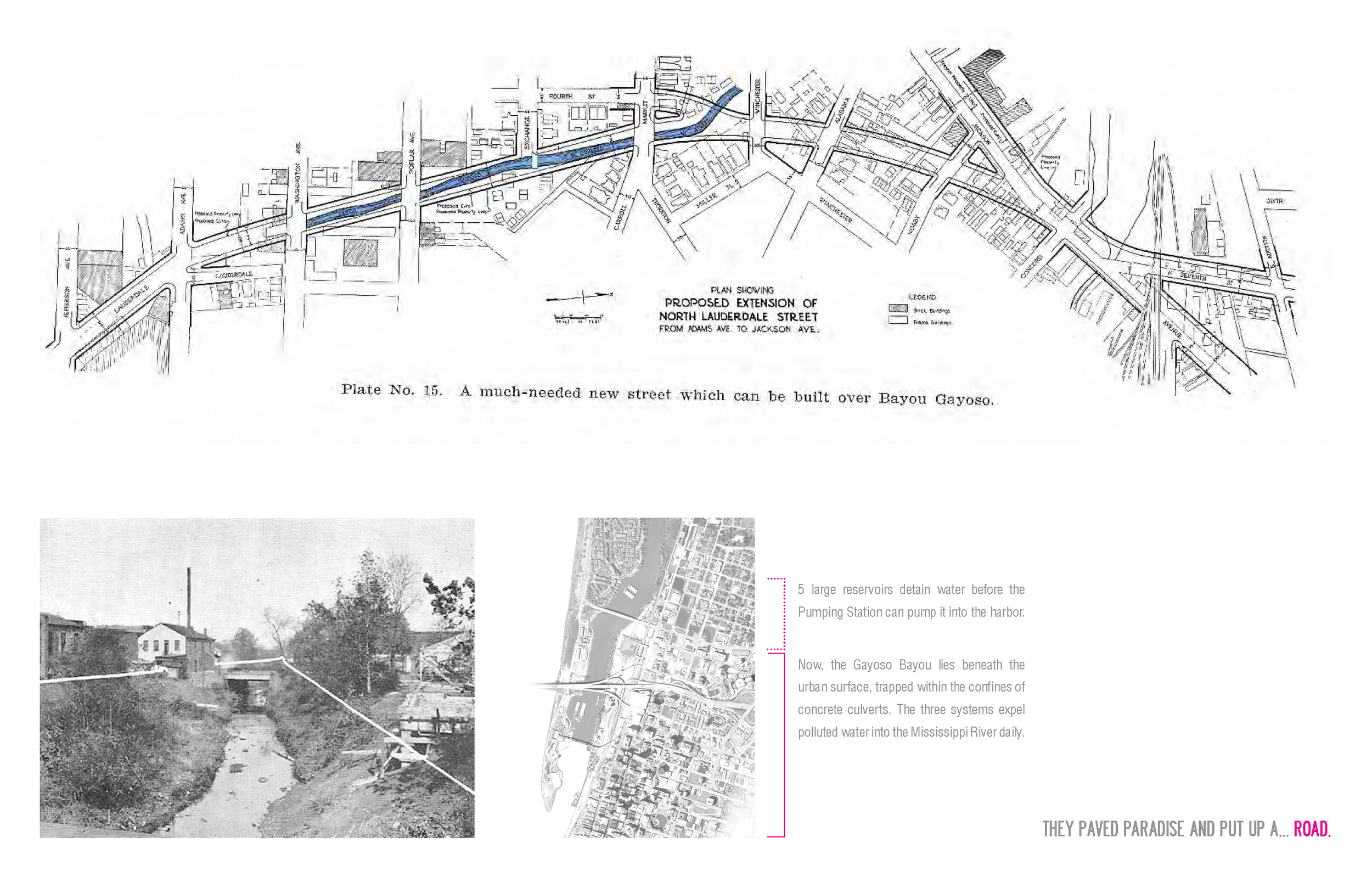

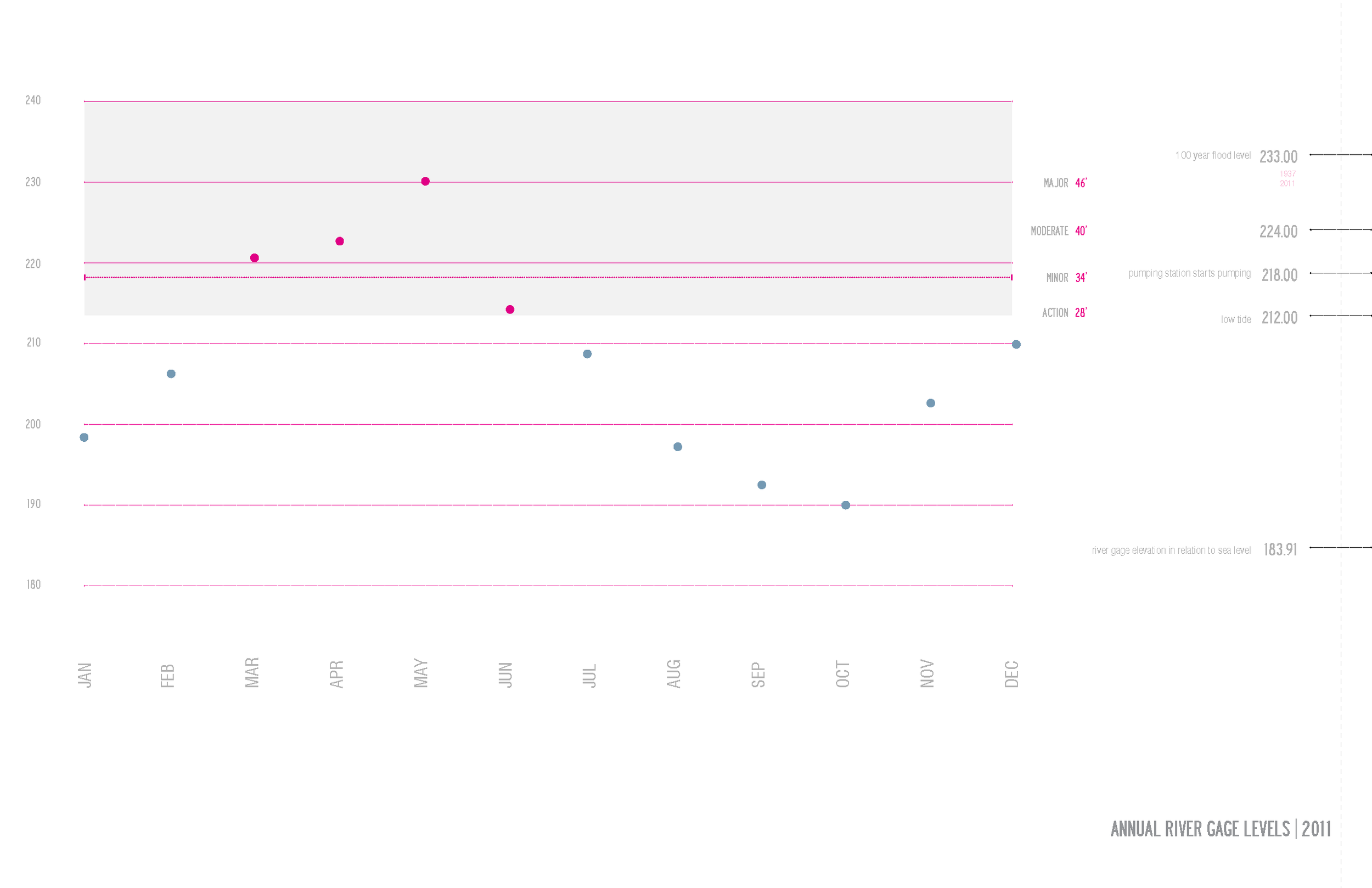

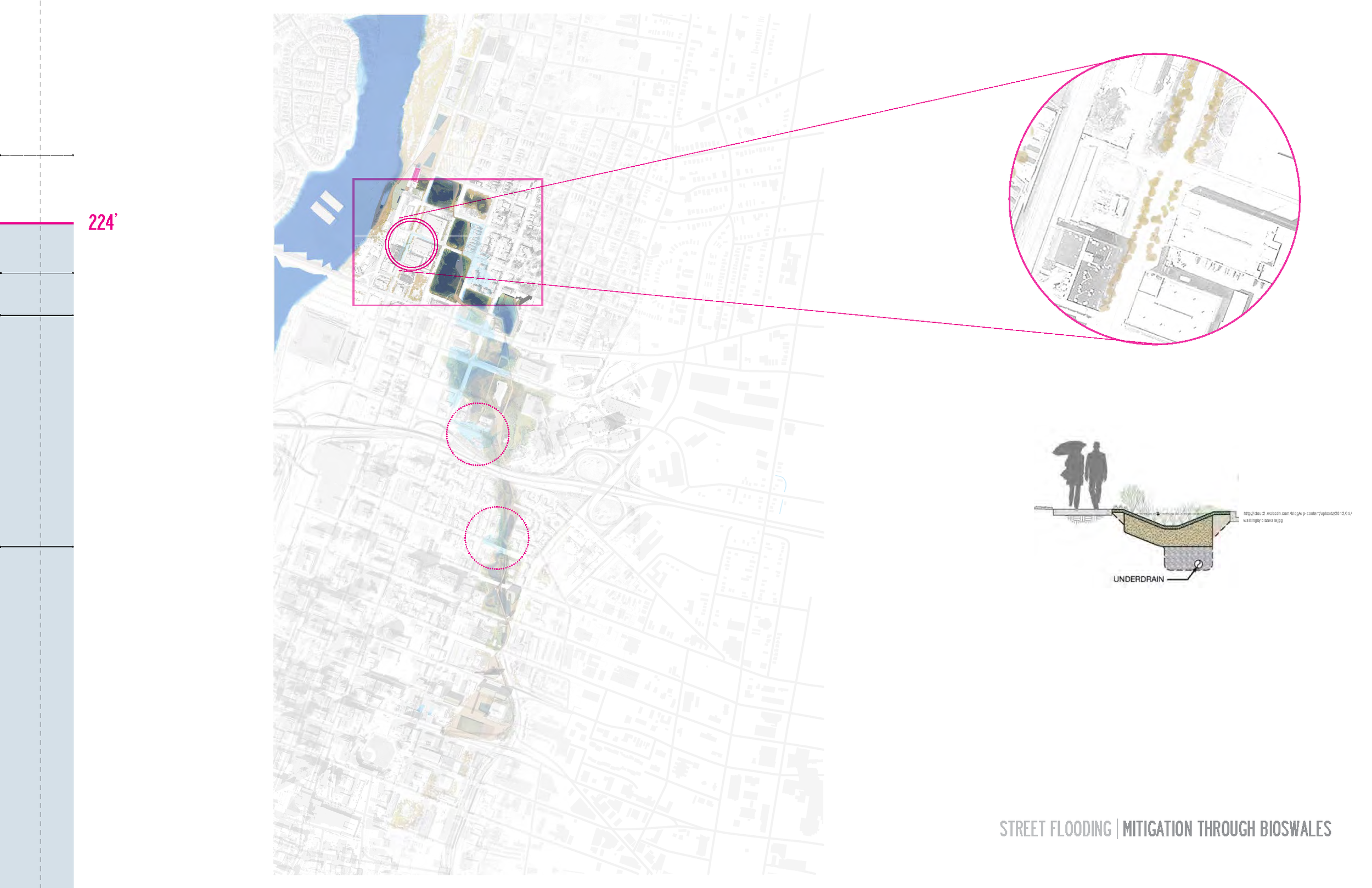

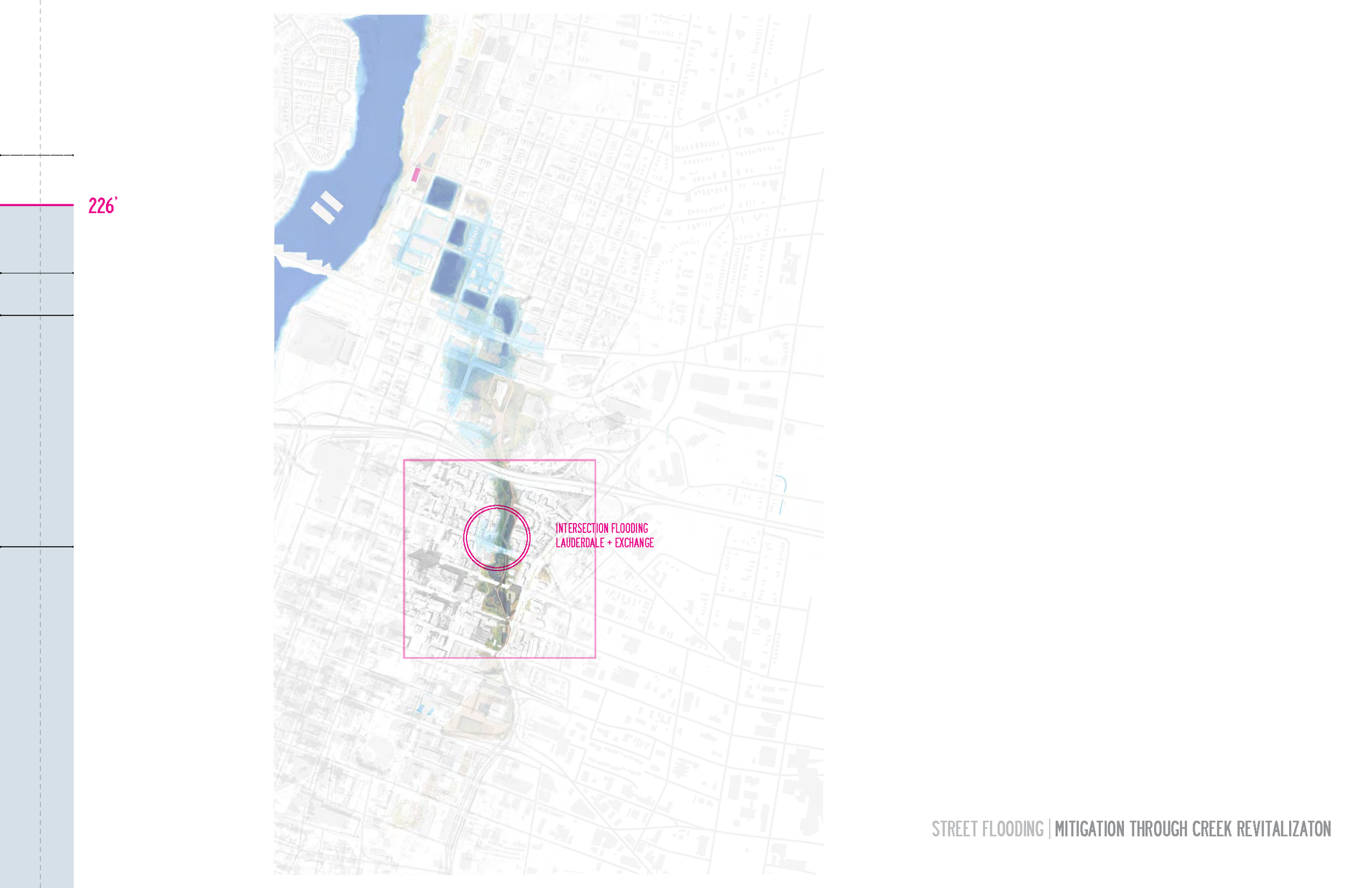

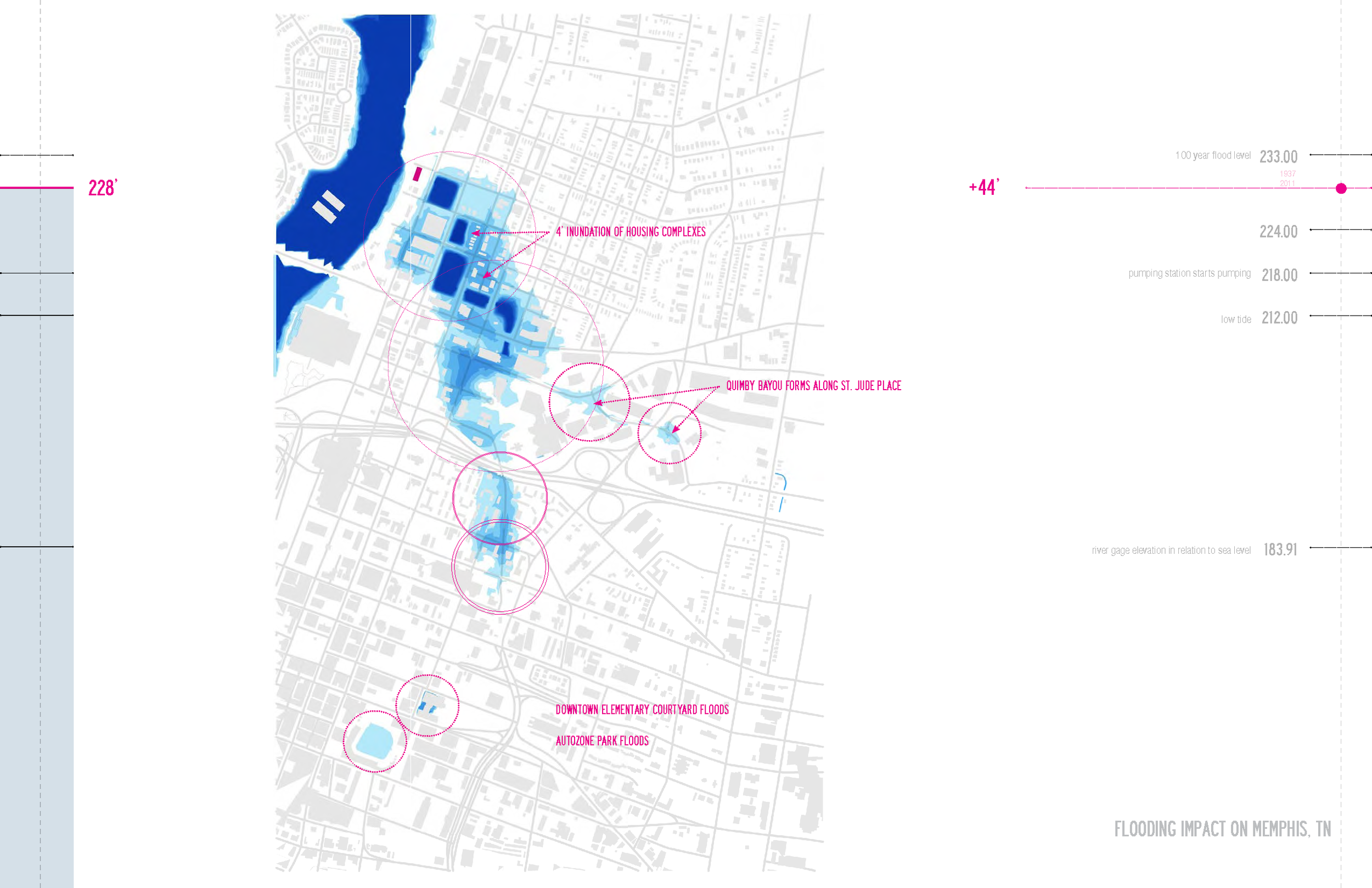

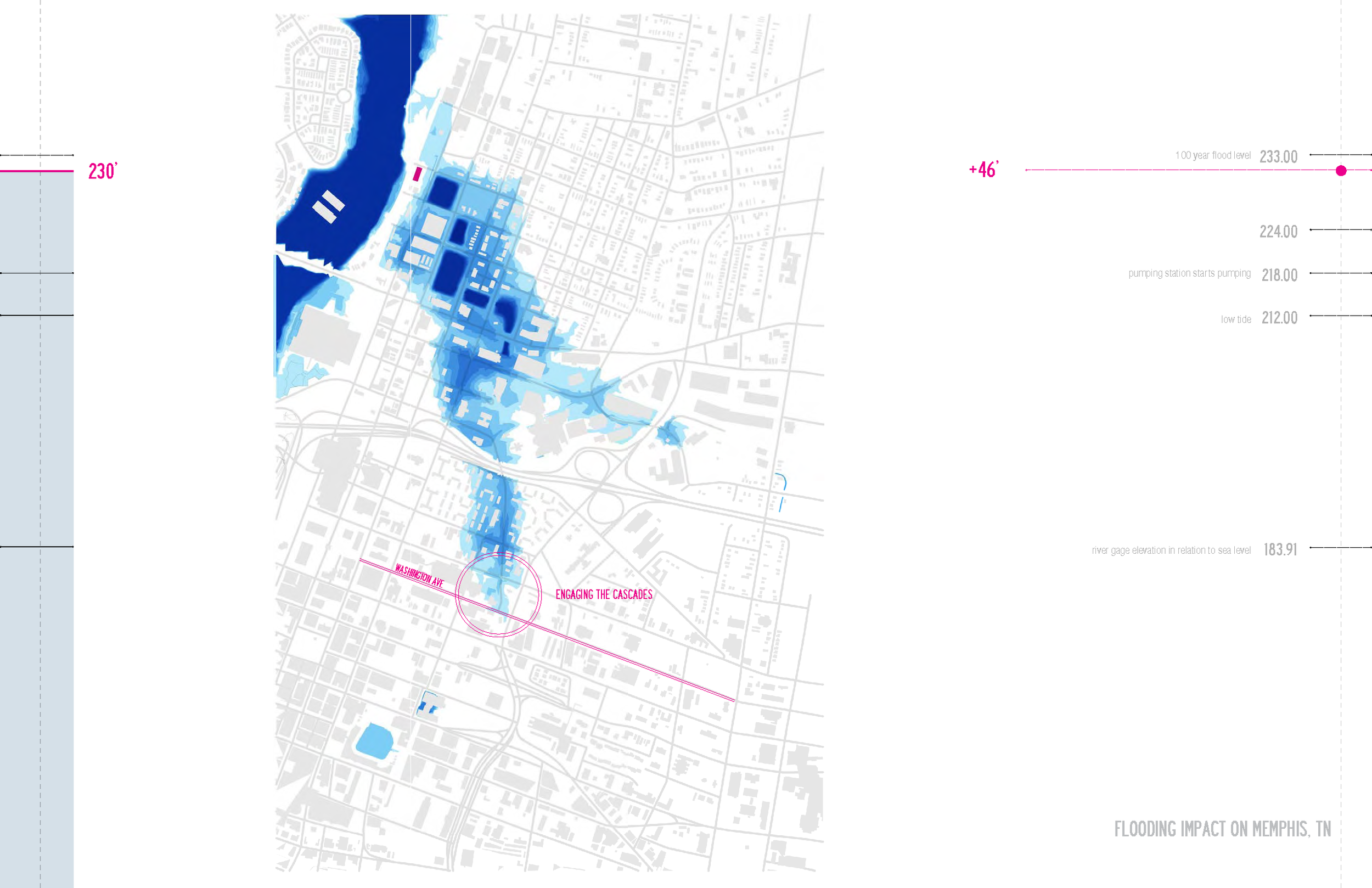

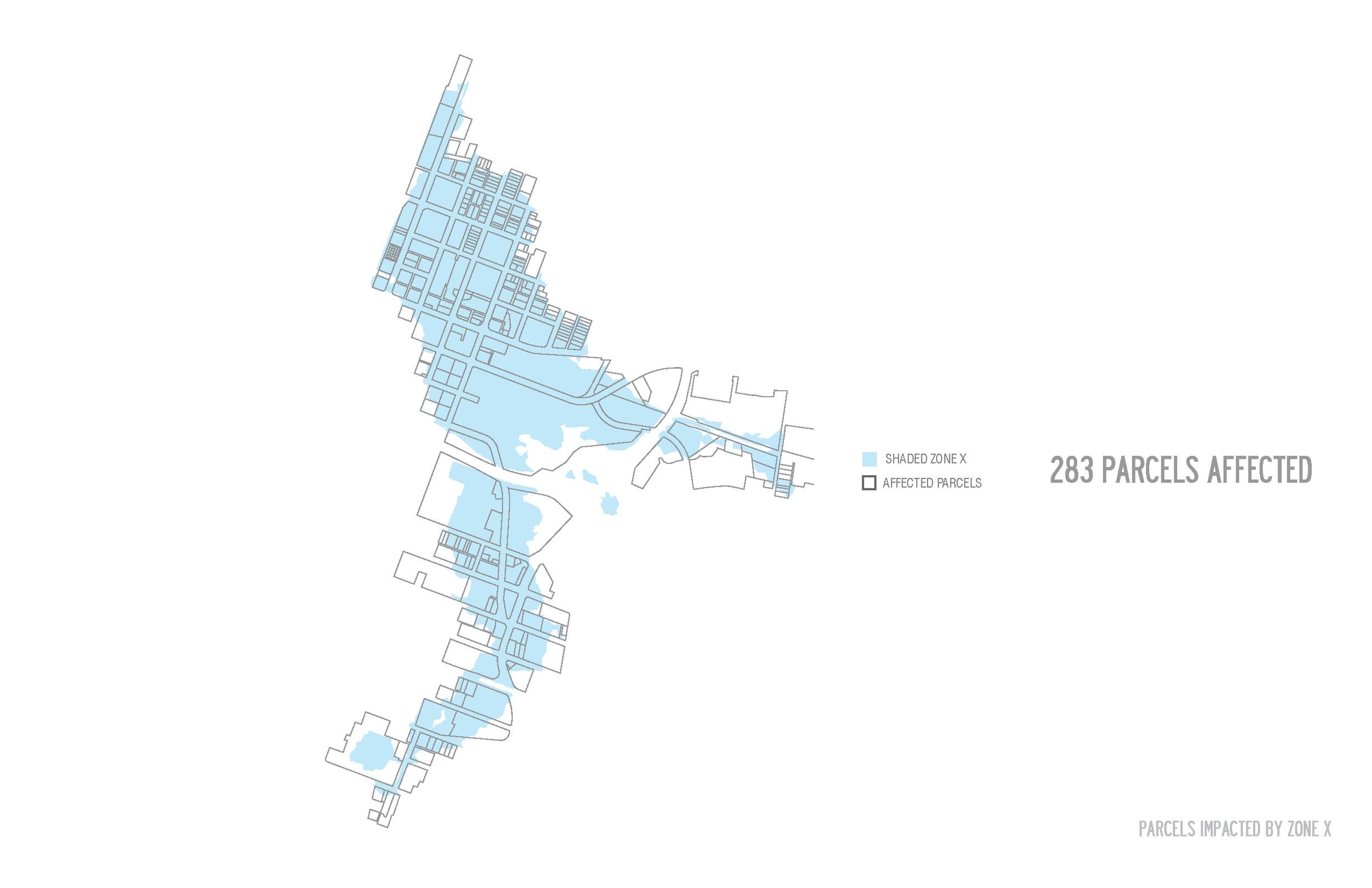

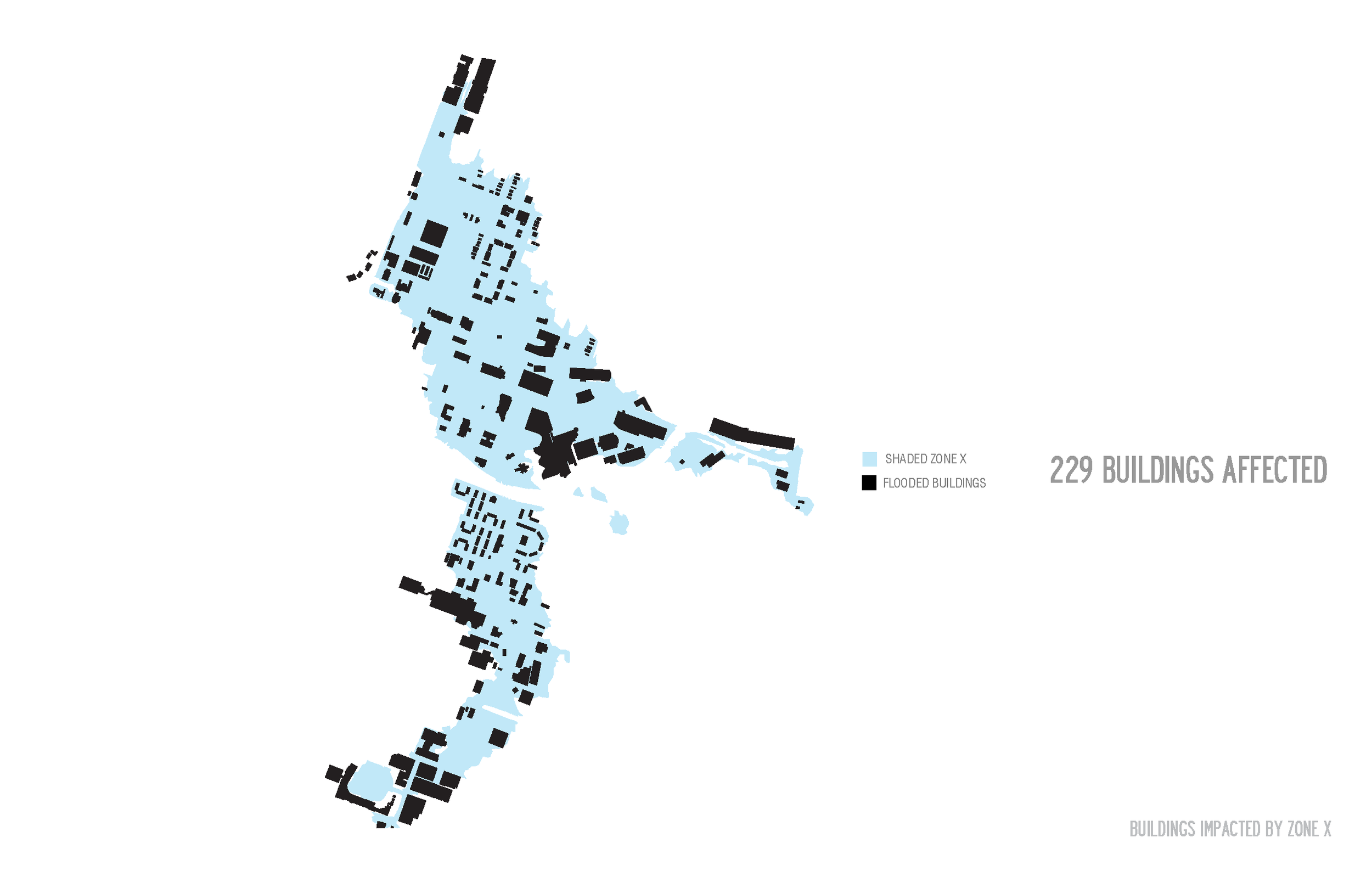

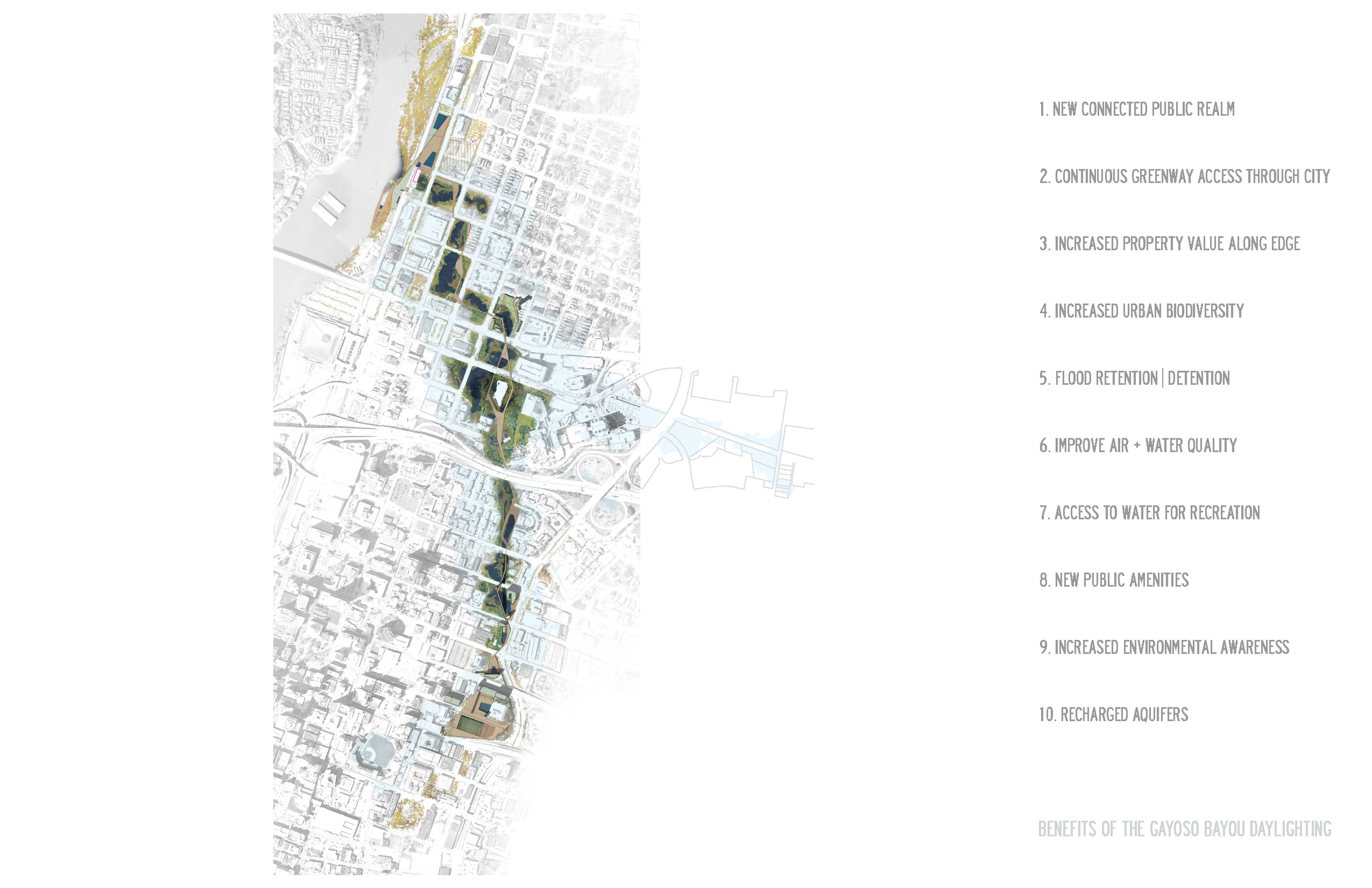

243 acres in Memphis, TN, is described as "Shaded Zone X" on the FEMA flood insurance maps. This area is in the center of the municipal boundary and has contains over 200 buildings, 25 roads and an underground water management system that people call "the cavern." After overlaying year and years of maps, I found that Shaded Zone X actually used to describe the watershed of the Gayoso Bayou, a bayou that used to serve as the eastern edge of "Downtown Memphis." Over the last century, the bayou has been covered and mechanized into an underground water management system that expels water from the city to the Mighty Mississippi through a pumping station built in the 1920s.

Deep Surface explores the potential of a revival of the Gayoso Bayou to serve as temporal landscape weaving throughout the cities landscape. A new development that considers the ecology of the place, the impending flood, and the earthquake liquefaction zone (which runs along where the bayou once ran).

Read more about this project on Archinect.

Latent Realities - Greg Spaw

Visualizing Forces of the Tennessee Valley Authority

Arch 425/525_Spring 2014

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, Tennessee

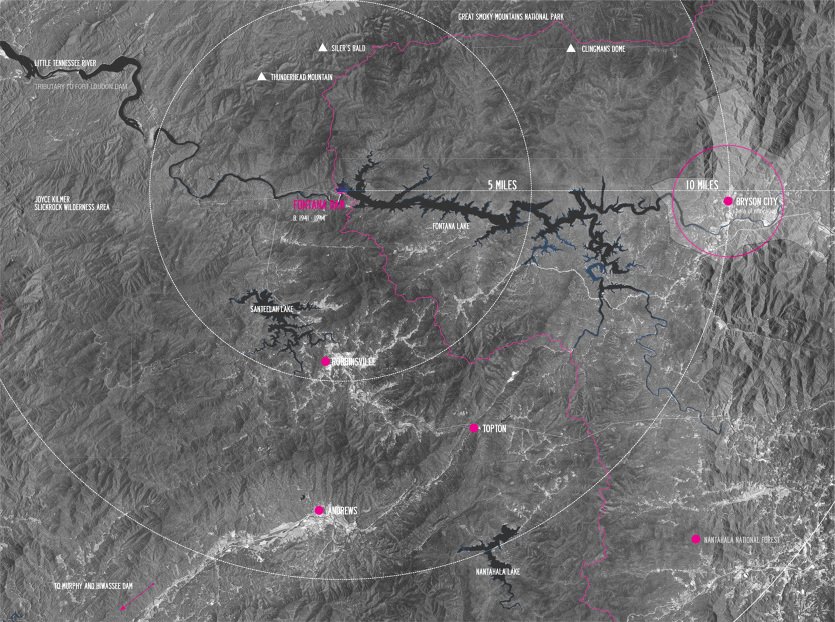

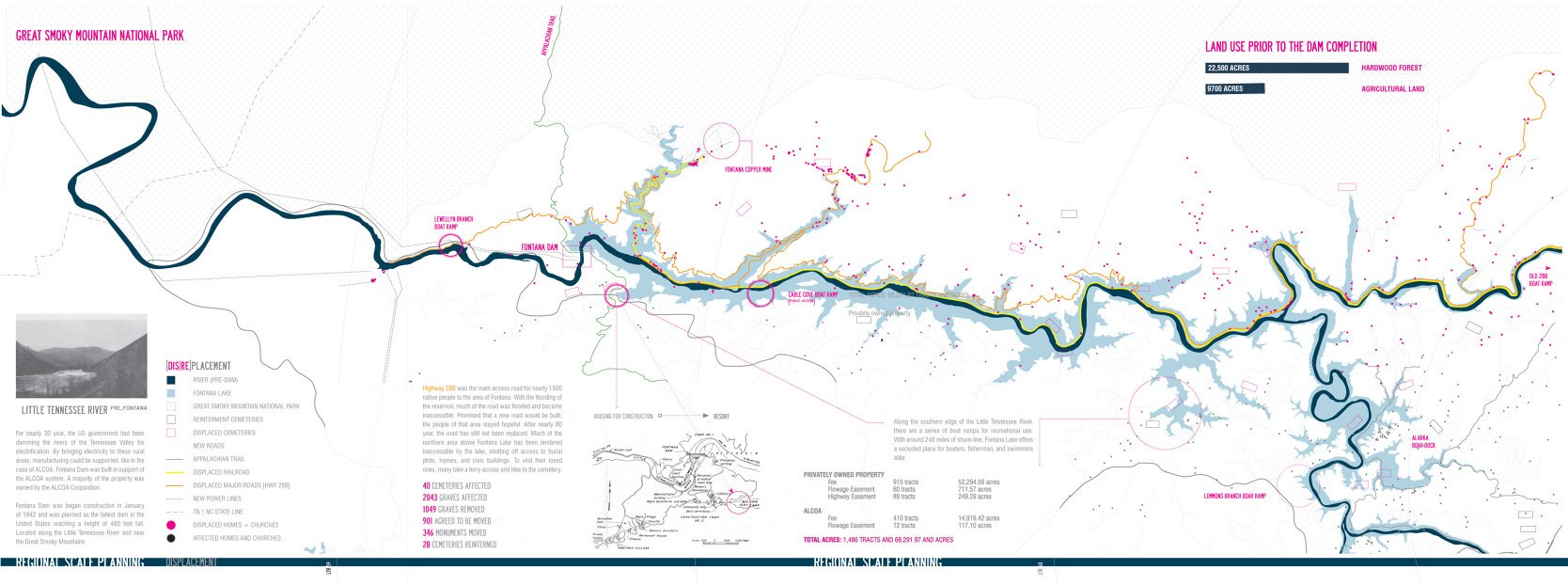

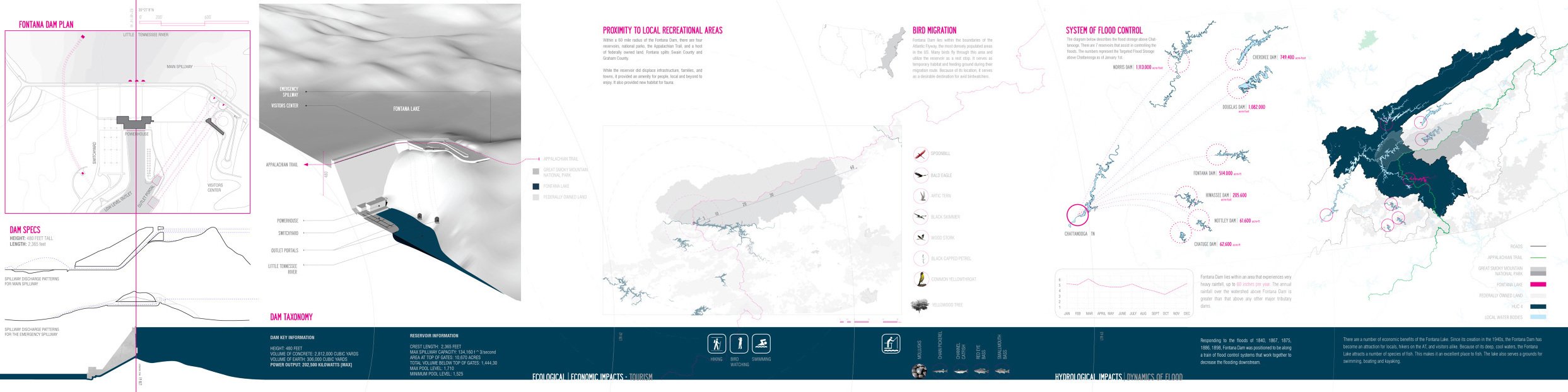

Latent Realities looks to explore the seen and unseen forces associated with the work of the Tennessee Valley Authority. Attention to framing will be essential as we look at how the network of associated projects have impacted the region’s settlements, hydrology, agriculture, manufacturing, infrastructure... etc. Tools such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) will be critical to our analysis, especially when investigating issues of reciprocity between ecology, economy, and energy at a macro scale. While the course purview is locationally focused, there will be opportunities to discuss concurrent concerns facing developing territories and the role infrastructural insertions can serve in creating design for intelligent landscape / urbanism. The seminar will give students in the architecture and landscape programs a series of new skills as well as a greater understanding of how complex systems interrelate. The collective output should lead to a body of publishable original research.

Organized as a sequence of topics the elective will include readings, presentations, and an extended study tour that focuses on visualizing / mapping the relationships between the historical landscape / ecology, TVA projects of 1930s-1970s, and the region as it stands today.

Selected Works